If you want one financial habit that outperforms almost everything else, it’s not timing the market — it’s time in the market. Compound interest is the engine that turns small, regular savings into large sums over time. This post explains how compounding actually works, shows concrete examples with numbers, and gives a simple, automated plan to start building real wealth with minimal effort.

What is compound interest?

Compound interest means you earn returns on both the money you add and on the returns that money already earned. Think of it like rolling a snowball down a hill: it starts small, then grows faster as it rolls. The longer you leave it rolling, the bigger it gets — and that’s why starting early matters more than the exact dollar amount you begin with.

The formula — and why you don’t need to memorize it

The future value of regular contributions is: FV=P×(1+r)n−1rFV = P \times \frac{(1+r)^n – 1}{r}FV=P×r(1+r)n−1

Where:

- PPP = periodic contribution (e.g., monthly),

- rrr = periodic interest rate (annual rate ÷ 12),

- nnn = total number of periods (months).

You don’t have to calculate this by hand — a spreadsheet or online compound calculator will do it — but understanding the inputs (time, rate, contribution) is crucial.

Real numbers — the effect of time (carefully calculated)

Using a conservative long-term return of 7% annual, compounded monthly (r = 0.07 / 12):

Example A — $100 per month for 40 years (age 25 → 65)

- P=$100P = \$100P=$100; r=0.07/12=0.0058333333r = 0.07/12 = 0.0058333333r=0.07/12=0.0058333333; n=480n = 480n=480.

- Plug into the formula → Future value ≈ $262,481.34.

- The Proven Strategy Behind Smarter, More Confident Financial Planning

- FIRE Movement 101: Can You Really Retire Early?

- How Delaying Your Retirement Savings Can Cost You Big

- Think Your Government Pension Is Enough? Here’s Why It’s Risky

- Retirement Planning: How to Win Big in Your 20s—and Catch Up in Your 40s

Example B — $200 per month for 40 years

- Double the contribution to $200/month → Future value ≈ $524,962.68. (Doubling contributions doubles the result.)

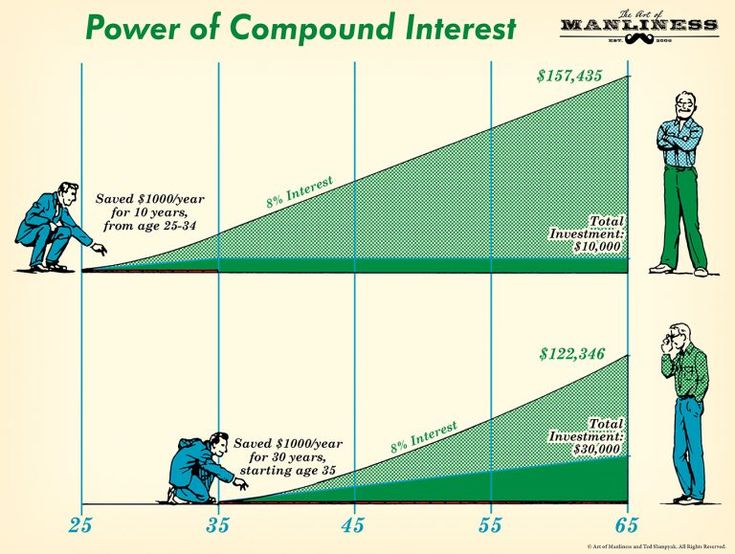

Comparative example — start later with same contributions

- $200/mo for 30 years (start at 35 → 65): ≈ $243,994.20.

- $200/mo for 20 years (start at 45 → 65): ≈ $104,185.33.

To match the 25→65 outcome of $524,962.68 while starting at 35 (30 years) you’d need to contribute about $430.31/month.

To match it starting at 45 (20 years) you’d need roughly $1,007.75/month.

Conclusion: Ten extra years of contributions (or, more precisely, ten extra years of compounding) is the single most powerful lever.

The lazy, practical plan (how to make compounding do the heavy lifting)

- Automate contributions — set up a recurring transfer (even $50/month). Automation beats perfect timing.

- Capture employer match first — if you have a 401(k) or similar with matching, contribute at least to the match. It’s immediate, guaranteed return.

- Choose low-cost broad-market funds — index funds or ETFs keep fees low (fees compound against you).

- Reinvest dividends — keep all returns compounding inside the account.

- Ignore short-term noise — check once a quarter or yearly. Let compounding run.

- Increase contributions with raises — every 1% raise = more passive future wealth.

Download: Compound Interest Calculator and Starter Kit — 1-page checklist + sample contribution plan.

Common objections & short answers

- “I don’t have enough to start.” Start with any amount. Small monthly contributions add up astonishingly over decades.

- “Markets are risky.” Risk matters for short-term goals. For long horizons, equities historically reward patience. Balance with bonds as you approach your goal.

- “I want higher returns.” Higher returns usually mean higher volatility. A consistent, low-cost approach is the dependable route.

How Soon Should You Start Investing? The Best Age Revealed